by John Donovan Feb 6, 2020

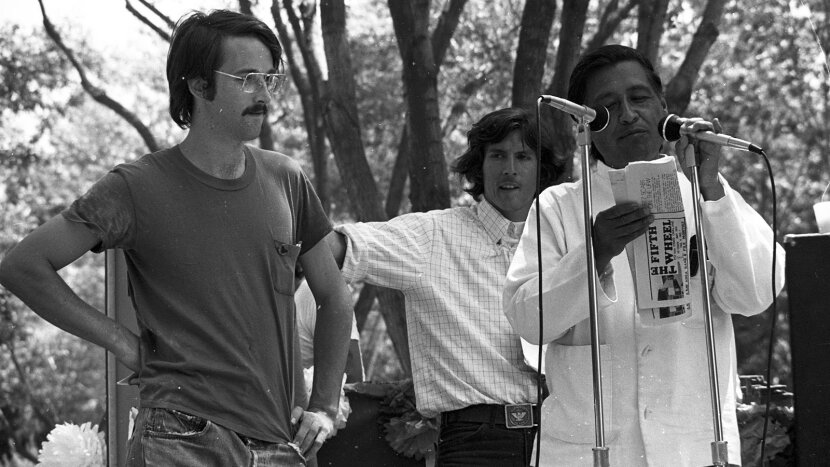

Cesar Chavez is perhaps best known as an American union builder during the furious 1960s and a relentless advocate for the rights of abused farmworkers. Library of Congress

The fight for human rights is never done alone. It’s borne by a multitude of visionaries, carried on by armies of believers and waged in a variety of ways. Through, for a few examples, the quiet and peaceful dignity of Mahatma Gandhi. The soaring eloquence of Martin Luther King Jr. The fervor of Susan B. Anthony. The certitude of Malcom X. The unbending reason of Nelson Mandela. The persistence of young Greta Thunberg.

Among those icons old and young, past and present, a special place is reserved for Cesar Estrada Chavez, whose humility and resolute belief in La Causa made him a hero to millions.

“Why were they drawn to him?” asks Marc Grossman, Chavez’s speechwriter and personal aide who now is the communications director for the Cesar Chavez Foundation. “Because he had great faith in them. He had faith they could do great things.”

Who Was Cesar Chavez?

Chavez is perhaps best known as an American union builder during the furious 1960s and a relentless advocate for the rights of abused farmworkers. But the way in which he carried out his work, and the people he reached with his message of hope, made him so much more.

He was a devout Catholic who believed in the goodness of his fellow humans and the power of nonviolent resistance. He was friends with Bobby Kennedy. He exchanged telegrams with King.

And to this day, Cesar Chavez remains a darling of America’s counterculture, a soft-spoken, sly-smiling, immovable object standing in the path of the country’s rich and powerful.

The child of Mexican American parents, Chavez was born in 1927 in Yuma, Arizona, into the back-wrecking life of a migrant farm family in the Southwest United States. He and many others commonly worked 10- to 12-hour days, often bent over a short-handled hoe — el cortito — for wages that would barely keep them alive. He estimated that he attended 65 different schools as a kid. He never got past eighth grade.

Chavez enlisted in the U.S. Navy after the end of World War II, before it was desegregated, but soon returned to California, where he started a family of his own. By the early 1950s, he was introduced to organizers in the Community Services Organization, and by the late ’50s he had become its national president.

By the early 1960s, Chavez already was in full dispute with the moneyed growers who saw him and his swelling group of followers as a threat to their financial well-being. He traveled the fields of California, signing up workers to join his fledgling National Farm Workers Association (NFWA), later to become the United Farm Workers.

And soon, bolstered by his belief in La Causa, Chavez would transform the lives of thousands.

Cesar Chavez is seen speaking at the Delano United Farm Workers rally, in Delano, California in June 1974. Calliopejen1/Wikimedia Commons/(CC BY 3.0)

Fighting the Good Fight

Though Chavez lacked a full, formal education, he was a voracious reader. He followed Gandhi and King and took from them lessons of nonviolence. He also read the works of union organizers like Eugene V. Debs. His belief in the workers, and their worth, pushed him. And their belief in him sustained his work.

“You know, many people, for a hundred years before Cesar Chavez, tried and failed to organize farmworkers. People who had a lot more resources and money and had a much better education, tried and failed. For a hundred years,” Grossman says. “And he succeeded, I think, because he was one of them. It was not an academic pursuit for him.”

Chavez endured government investigations and death threats from the rich and powerful. He often traveled with two fierce-looking German shepherds — Boycott and Huelga (Strike) — who became both friends to Chavez and deterrents to those who might wish him harm. (They also were an inspiration. He credited his dogs with his decision to become a vegan, and he became an animal rights activist later in his life.)

As he did in the fields as a young man, Chavez put in long, hard hours organizing workers, traveling from town to town, pushing for better wages, insurance and improved working conditions. He employed the threats of boycotts and strikes — and, in fact, went beyond mere threats — to try to better the lives of those he represented.

In 1965, Chavez and the NFWA joined forces with a group of Filipino grape workers in the Delano (California) grape strike. It lasted five years and included a boycott of table grapes that spread throughout the nation. Chavez insisted — with an acute awareness of the violence that roiled the country that decade — that the protest remain nonviolent. But as it wore on, many workers grew impatient.

To focus strikers on staying strong without using violence, and to show those throughout the country their resolve, Chavez went on a 25-day fast. Thousands streamed into the tiny windowless room near Delano to see him during his fast. He lost 35 pounds (15 kilograms).

King sent a telegram, which said in part:Your past and present commitment is eloquent testimony to the constructive power of nonviolent action and the destructive impotence of violent reprisal. You stand today as a living example of the Gandhian tradition with its great force for social progress and its healing spiritual powers.

Bobby Kennedy was there as Chavez finally broke the fast, calling him, “one of the heroic figures of our time.”

In a statement, Chavez said, “To be a man is to suffer for others. God help us to be men.”

It took some more time, but in 1970, grape growers signed a contract with unions that, for the first time, provided workers better pay and benefits.

Caesar Chavez at the national headquarters of the United Farm Workers Union, talking with grape boycott leaders in Keene, California. Library of Congress

Beyond the Union Battle

Chavez stepped outside union activism, too. He came out strongly against the Vietnam War in the 1970s and in the ’80s (and perhaps even earlier) was active in the struggle for gay rights.

The Delano fast was not the only hunger strike that Chavez would undertake over his long career. He went for 36 days without food in 1988 to protest working conditions, including the threat that pesticides posed to the workers. (He was, in effect, an early environmental activist, too.)

Chavez continued to work and organize for the UFW throughout his life. He was in Arizona in 1993, helping to defend the union in a lawsuit, when he died, peacefully, at the home of a longtime friend. He was 66.

Some 45,000 people attended his funeral in Keene, California, now the site of the Cesar E. Chavez National Monument.

Throughout his life, Chavez fought for farmworkers. But he came to realize — or, perhaps, he knew it all along — that the fight was larger than that between workers and employers. “And that meant tackling the dilemma in the community,” Grossman says. “It had to be more than wages, hours and working conditions. It had to be more than money for your own people.”

In 1984, in a carefully crafted speech in front of the Commonwealth Club

in San Francisco (he rarely spoke from a script), Chavez laid out his

vision. Buoyed at the time by recent UFW successes and impending

demographic changes that promised to strengthen Hispanic political

power, Chavez sounded less like a union organizer than a full-blown

civil rights icon. An excerpt:Once social

change begins, it cannot be reversed. You cannot uneducate the person

who has learned to read. You cannot humiliate the person who feels

pride. You cannot oppress the people who are not afraid anymore.

Our opponents must understand that it’s not just a union we have built.

Unions, like other institutions, can come and go. But we’re more than an

institution. For nearly 20 years, our union has been on the cutting

edge of a people’s cause — and you cannot do away with an entire people;

you cannot stamp out a people’s cause. Regardless of what the future

holds for the union, regardless of what the future holds for

farmworkers, our accomplishments cannot be undone. “La Causa” — our cause — doesn’t have to be experienced twice.

His Lasting Legacy

Today, the University of California-Berkeley has a student center named after Chavez. High schools, elementary schools, streets and parks bear his name. So does a Navy ship. In 2003, the U.S. Postal Service issued a stamp with his likeness. President Barack Obama christened the national monument in 2012 where Chavez is now buried.

More, the thousands of people who flocked to meet him, the millions more who knew of him or have learned about him, continue to carry on his work and his dreams. Grossman cites a couple of examples off the top of his head: a young teacher in California who now is a supervisor in her school district. A young paralegal who now is a superior court judge in the state.

“He saw the greater good of helping people fulfill their dreams. And some of them were dreams that many of them didn’t even know they had,” says Grossman. “He really instilled hope and confidence in people who never had them before.”

The fountain at the grave marker of Cesar Chavez honors the United Farm Workers’ five martyrs, including Nan Freeman, Nagi Daifallah, Juan De La Cruz, Rufino Contreras and Rene Lopez. National Park Service NOW THAT’S INTERESTING In August 1994, a little more than a year after his death, Chavez was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom by President Bill Clinton in a ceremony at the White House. “The farmworkers who labored in the fields and yearned for respect and self-sufficiency pinned their hopes on this remarkable man, who with faith and discipline, with soft-spoken humility and amazing inner strength, led a very courageous life; and in so doing, brought dignity to the lives of so many others and provided us for inspiration for the rest of our nation’s history,” Clinton said. Chavez’s widow, Helen, received the award.