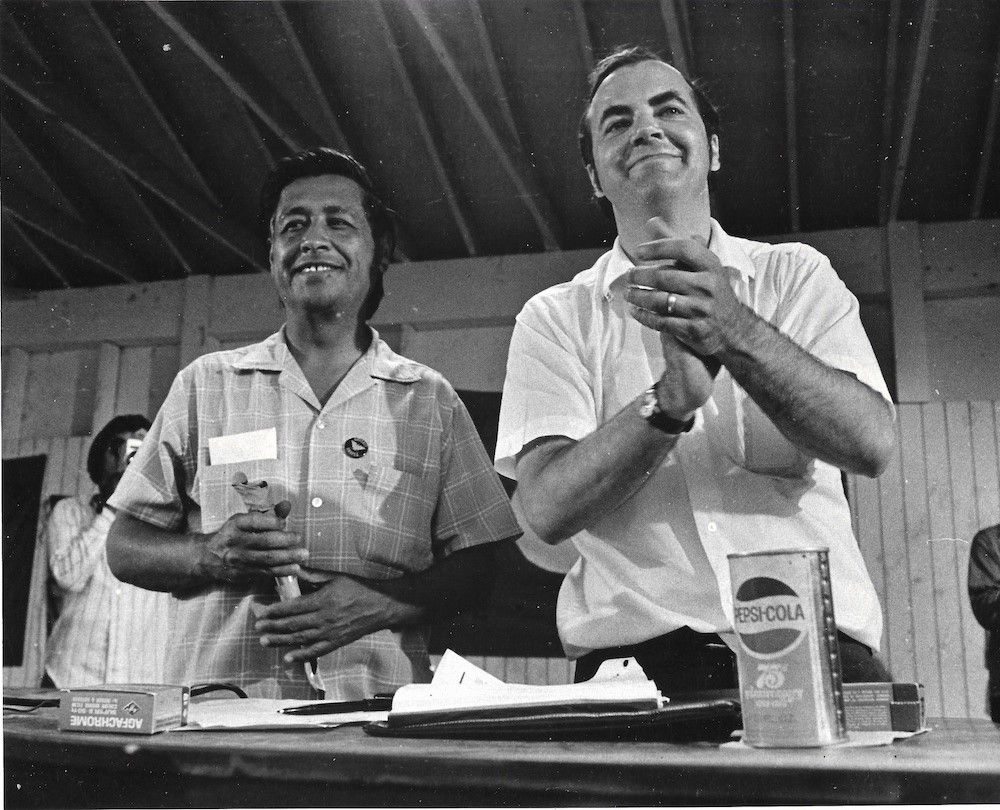

Rev. Chris Hartmire worked with Cesar Chavez and other early organizers before there was a farm worker union, and then selflessly dedicated himself for decades to building what became the United Farm Workers. He passed away peacefully at age 90 on Sunday, Dec. 18 at the Pilgrim Place Senior Community for retired clergy in Claremont, Calif.

Always humble and soft-spoken, Chris inspired countless women and men to activism and “servanthood” by dedicating themselves to the UFW and other good works.

After earning a civil engineering degree at Princeton University and becoming a naval officer in the mid-1950s, his life changed when he fell in love with working among impoverished low-income kids and in 1957 entered the famed Union Theological Seminary in New York City.

Born in Philadelphia in 1932, Wayne C. Hartmire Jr. grew up in the Presbyterian Church. After graduating from the seminary, Chris worked in an East Harlem parish running an inner-city ministry serving teenagers, mostly African American and Puerto Rican.

While there, in 1961 Chris joined a Freedom Ride challenging segregation in the Deep South. Riding buses down the East Coast to Tallahassee, Florida, Chris and his colleagues faced down menacing crowds of Whites armed with clubs and guns.

His integrated band of Freedom Riders was flying home from the Tallahassee airport when they tried eating there. The restaurant was being cleaned—permanently. Chris was one of a dozen activists who stayed to assert their right to service. An angry crowd grew outside the terminal. Chris’ group was arrested for unlawful assembly, unlike members of the mob.

Another calling awaited Chris in California. The Migrant Ministry began in 1920 in New Jersey when church women offered child and health care and recreation to migrant farm workers and their children. These were “middle class church people trying to do good for very poor people,” Chris noted. The ministry spread across the nation.

Chris joined a California Migrant Ministry summer program in Modesto in 1961 with other young people working with Central Valley farm worker kids. A grant let migrant ministry staff spend six weeks with Fred Ross and Cesar Chavez as they organized chapters of the Community Service Organization Latino civil rights group. “It was an eye-opening experience of poor people organizing for their own power,” Chris recalled.

“I was so young and green,” said Chris, who was 29. Cesar was 34 but looked younger. “It was agreed I’d work in Stockton with Dolores [Huerta] and Gil[bert] Padilla.” Chris was soon tapped to lead the California Migrant Ministry.

Cesar invited Chris to all CSO board meetings and conventions. Chris was “totally fascinated. Cesar was organizing me. In his mind, the migrant ministry was going to be of use to him some day.”

Chris was at the 1962 convention in the Imperial Valley town of Calexico when CSO rejected Cesar’s plan for an organization to unionize field laborers. Many urban CSO members thought Cesar’s notion was “pie in the sky,” Chris remembered. Agribusiness was one of California’s richest industries. Organizing farm workers would be controversial. Cesar resigned from CSO.

Traveling up the Central Valley from ministry headquarters in Los Angeles, Chris would stop by Cesar’s house on Kensington Street in Delano “to catch up on what was going on.” Cesar, his wife, Helen, and some of their eight children joined Chris at a spring 1962 ministry staff retreat at a rustic YMCA summer camp in the Sierra foothills near Bakersfield.

There, “Cesar was very open about what was going on, and the difficulties.” He talked about holding house meetings, chasing down worker leads, and “looking for [agricultural workers who] he could tell by their eyes and conversations that they wanted this so much that they’d pay dues, go on strike, and do whatever it took to build this union.” The ministry staff “knew this was an impossible task Cesar had taken on,” Chris observed. “But we believed he could do it.”

Cesar enjoyed “camaraderie” with the young Protestant clergy. Yet, Chris said “another part of him was always organizing and looking to the future”—when the migrant ministry could be “a valuable ally once things got difficult” by supporting strikes and eventually boycotts outside the fields and vineyards. “By this time, I wondered if Cesar knew no strike in agriculture would work without it spreading beyond the fields.” The California Migrant Ministry was part of the National Council of Churches. Cesar knew what churches did for the Southern civil rights movement.

Cesar asked Chris Hartmire to address the union’s founding convention in Fresno in September 1962, translating for him. Chris witnessed the dramatic unveiling of the iconic UFW black-eagle banner.

Cesar didn’t think strikes would happen for years. “It happened a lot sooner than he had expected,” Chris said, when Filipino grape pickers led by Larry Itliong struck Delano-area table and wine grape growers in September 1965, and asked Cesar’s mostly Latino union to join them.

Once the multi-racial grape strike broke out, followed by an international grape boycott, Chris’ migrant ministry was key in rallying support from faith activists across the U.S. and Canada—and from millions of consumers from all walks of life. This work was very controversial and divisive, sparking deep conflicts within churches in rural areas and elsewhere.

After the UFW won support from churches across the land and captured the country’s attention with vital help from the California Migrant Ministry, a national migrant ministry was created in 1971, the National Farm Worker Ministry, which continues to this day. Chris Hartmire was its first director.

Chris learned the meaning of servanthood from the farm workers, he said: “A servant gets into the lives of the people, washes their feet, and serves them. A servant joins with farm workers to be of service to them rather than bringing them services such as food or toys,” which the migrant ministry had done for decades.

Chris Hartmire devoted decades to servanthood with farm workers and championing other worthy causes. “Chris is a modern Christian revolutionary who spent his entire adult life focused on the needs of others,” said his longtime friend and colleague Rev. Gene Boutilier.

He was preceded in death by his beloved wife and partner, Pudge. He is survived by their children, John Hartmire, Jane Marks, David Hartmire, and Gordon Hartmire; nine grandchildren; and two great-grandchildren. A celebration of his life is planned for January at Pilgrim Place in Claremont.