“We don’t need perfect political systems; we need perfect participation.” - Cesar Chavez

United Farm Workers ¡Si, Se Puede!®

“We don’t need perfect political systems; we need perfect participation.” - Cesar Chavez

El Malcriado Special Edition, September 17-18, 2005

The 40th anniversary of the Delano Grape Strike was marked by two days of celebrations organized by the farm workers movement on Saturday and Sunday, Sept. 17 & 18, 2005. They honored the pioneers who walked out of Delano-area wine and table grape vineyards in September 1965.

Roughly 500 persons attended events in Delano on Sept. 17 that included panel discussions and a formal ceremony recognizing the 1965 strikers. For many, it was the first time they had seen each other in 30 years or longer.

The program went from 10 a.m. until 7 p.m. at the United Farm Workers’ “Forty Acres” at Garces Hwy. and Mettler Ave. just west of Delano. That evening, many UFW veterans gathered for a sentimental reunion at People’s Bar on Garces Hwy. in Delano, the strikers’ unofficial after-hours hangout during the 1960s.

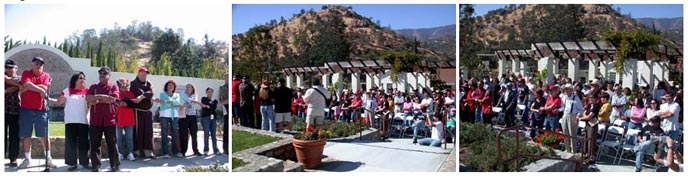

Sunday’s gathering at the National Chavez Center in La Paz, Cesar Chavez’s burial site and the farm workers’ Keene, Calif. headquarters, recognized the contributions of union staff and volunteers from the ’60s grape strike and boycott.

Organizers understood these events could easily have attracted thousands of farm worker activists and supporters. But that would have made it impossible to stage a more intimate reunion honoring individual strikers and former staff. So sponsors labored for months to locate and invite all grape strikers and movement volunteers who served during the five years of the original strike and boycott, from 1965 to 1970.

Further observances marking 40-year milestones in the five-year grape strike and boycott are being planned. The next observances will soon be scheduled for April 2006, to remember the Delano-to-Sacramento march by striking grape workers in March and April 1966. Further observances will chronicle other important benchmarks in the history of the farm workers movement such as the 1970 Salinas vegetable strike and the 1973 grape strike.

(See inside for a guide and map depicting historic locations from the 1965-’70 walkouts and boycott both at the Forty Acres and in Delano.)

* * *

Saturday in Delano

After a welcome from UFW President Arturo Rodriguez, most of the day in Delano on Sept. 17 was dedicated to well-attended panel discussions on the grape strike and boycott. They took place inside the same union hall at the old UFW field office on the Forty Acres where Delano grape growers assembled on July 29, 1970 to sign their first union contracts after five years of strikes and a three-year international grape boycott.

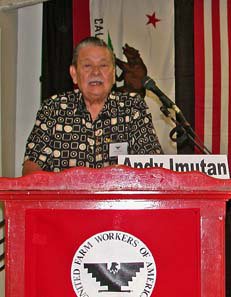

The morning panel. Moderated by Teatro Campesino founder Luis Valdez, it covered the strike itself. Discussing the decision to strike by Filipino American members of the Agricultural Workers Organizing Committee (AWOC) was panelist Andy Imutan. Recounting the decision to join the walkouts by the mostly Latino National Farm Workers Association (NFWA) was Esther Uranday. Robert Bustos talked about the 1966 peregrinacion (march) from Delano to Sacramento. And Kathy Murguia spoke of the role of volunteers who came to the strike. Many members of the audience approached microphones set up on the floor to make their own comments after the panelists’ presentations.

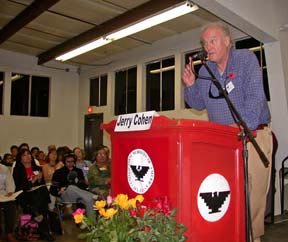

The afternoon panel. The first grape boycott was the subject of the second panel moderated by LeRoy Chatfield. Panelists included Marcos Munoz, who talked about his experiences after he was sent out to organize the boycott far from California; Virginia Rodriguez, who discussed the boycott from the perspective of volunteers in the cities; Dolores Huerta, who related how the boycott built coalitions with labor, political, student and community activists; Chris Hartmire, who spoke about the boycott and the religious community; and Jerry Cohen, who described events leading up to the signing of union contracts by Delano-area table grape growers. Audience comments also followed.

Personal recognitions. During a moving recognition ceremony, hundreds of former strikers and volunteers?some accompanied by family members?stepped forward as their names were called to receive specially framed commemorative black-eagle union flags featuring the words, “40th Anniversary Celebration, Delano Grape Strike, 1965-2005.” A list was posted containing the names of known strikers who have passed on.

The program ended with Luis Valdez and the Teatro leading the farm worker veterans as they linked arms and sang union songs, including “Solidaridad Para Siempre,” “Nosotros Venceremous” and “De Colores.” (The Teatro also performed at breaks during the program.) Lunch and dinner were served in the tree-shaded park outside the hall, two of many opportunities during the day for old friends and colleagues to reunite and catch up with one another.

* * *

Arturo Rodriguez, president of the UFW, kicked off the reunion.

Forty years ago brave men and women walked out of Delano-area vineyards and sparked a revolution in social and political consciousness, first among farm workers and then among millions of other Americans who never worked on a farm. These strikers were central players in a union that would be described by friends and foes alike as more than a union.

In a 1984 speech Cesar Chavez said, “The message was clear: If it could happen in the fields, it could happen anywhere–in the cities, in the courts, in the city councils, in the state legislatures.

“I didn’t really appreciate it at the time,” Cesar said, “but the coming of our union signaled the start of great changes among Latinos that are only now beginning to be seen.”

Yet those revelations came much later. On this 40th anniversary, it is important to remember that courage is not doing what comes easy. It is doing what comes hard. Forty years ago these strikers did the impossible by challenging the awesome power of California agribusiness.

Today, organizing farm workers is a difficult and daunting task. The challenges are formidable. But they are nothing compared to the obstacles facing our Latino and Filipino brothers and sisters four decades ago during those fateful days.

Today, we have a state law that is supposed to encourage and protect the right to organize. We have the confidence that comes from 40 years of experience in organizing. Forty years ago, the grape strikers were struggling against history. For 80 years, every organizing attempt had been defeated. Every strike had been crushed. Every union had been vanquished.

The only law those men and women knew was the law of the jungle. Abuse, contempt and violence against strikers were commonplace. All the social and political institutions in rural California were solidly allied with the growers.

In the face of such opposition, the Delano strikers were truly pioneers.

Let me also pay tribute as an organizer to the long line of tradition that links the past to the present. Those men and women who walked out of the vineyards and waged the nonviolent battles of the 1960s?and those who joined the struggle?did what great organizers do. They passed on what they learned from one person to another, from one generation to the next. That’s how I was touched.

There was a whole group of men and women from many places and backgrounds who put everything they had into this movement. It was their courage, skill and dedication that allowed this union to beat the odds and do what had never been done before. Today we are building upon that legacy.

All of you, strikers and volunteers, picketers and boycotters, no matter who you were, where you came from or where you ended up?you were all part of making history.

* * *

Saturday in Delano

Luis Valdez is founder and director of Teatro Campesino. He was also a picket captain in the 1965 strike.

As a young boy I worked for the Schenley farm in Delano. I guess one of my earliest memories came from this place and it wasn’t a pleasant one at all. One day as I was working the fields I was stung by a wasp. The sting was so severe that it left me blind for a whole day.

And so, many years later when I had the chance to strike against Schenley in 1965, I did it without any hesitation. I picketed with the rest of them and with a lot of satisfaction. However, I knew there was more that I could do.

One day I spoke to Cesar about expressing La Causa in artistic terms and he said, “It’s great, but there is no money, no actors, no theatre, no place to rehearse and no time to rehearse. Do you still want to do it?” Well, with an opportunity like that how could I refuse?

Although there were all those factors against starting Teatro Campesino, I didn’t let that stop me because I knew it could be a very effective outlet for people to become aware of what was happening in Delano.

So one day I took my scripts down to the Pink House where a lot of the workers were gathered. Dolores was there as well, and they just started improvising with what I had written and out of that Teatro Campesino was born. I am never going to forget that day because an explosion occurred in the kitchen and it might have been a sign of what we had just created: something very explosive and very powerful.

This strike was the inspiration for the Chicano movement. Many, if not most, writers and Chicano artists took something from the Delano strike and it is due to all the sacrifices that all the strikers made back in 1965.

I have had many experiences in the past 40 years including, working on Hollywood sets. But if it hadn’t been for the experience of being a picket captain in Delano and standing up to the face of those cabrones (the growers), I would not have been able to stand up in the face of the pinche producers in Hollywood.

* * *

Andy Imutan is one of the original strikers from the 1965 walkouts who started it all. He was a leader of AWOC and later a vice president of the United Farm Workers, formed by the merger of the largely Filipino AWOC and the mostly Latino NFWA. Imutan was also in charge of the Baltimore and New York boycotts, and was UFW director in Stockton and Delano.

My name is Andy Imutan and I am one of the original Filipino workers who went on strike in 1965. I am now only one of two living Filipino workers from that era as most of my brothers have passed away. The one thing that does remain is their legacy and their fight for a just cause.

The whole movement began in Coachella that same summer [of 1965]. That’s when a group of Filipino workers went on strike demanding that their wages be increased from $1.10 an hour as well as better living conditions. Finally, after 10 days of picketing we finally accomplished what we had set out to do?we increased our wages by 30Ë an hour. The victory was more grandiose, not so much for the wage increase but for its significance at defeating the growers. We knew then that we could accomplish a lot more.

As I look back, I don’t think we could have accomplished such victory in Coachella had it not been for the leadership of our brothers Ben Gines, Pete Manuel and Larry Itliong, who were all instrumental in that victory.

After a successful first strike we did it again, this time in Delano where wages were also starting out at $1.10 an hour. However, the struggle became a lot harder when Mexican workers started crossing our picketlines. There was no unity between the Mexicans and the Filipinos. The growers were very successful in dividing us and creating conflict between the two races. Although we tried to discourage and reason with the Mexicans that this was just hurting everyone, we weren’t able to convince them.

So Larry Itliong and I decided to take action by seeing Cesar Chavez, the leader of the National Farm Workers Association. We met to come up with a plan that would be beneficial for everyone, including the Mexican workers. However, Chavez said his organization wasn’t ready to go on a strike. It took several discussions and a lot of faith, but finally the Filipinos and Mexicans joined as one on September 16, to picket the Delano growers. On March 17, 1966 we set out on a march from Delano to Sacramento that initially only had 70 farm workers and volunteers. But by April 11, as we climbed the steps of the state Capitol, there were 10,000 supporters who had joined us in the cause.

A few months later our union, AWOC, and the NFWA joined as a single union. Out of this union the United Farm Workers was born. It was a very exciting time as we knew the potential when we joined together not as competitors but as true brothers joined in a very legitimate cause.

* * *

Esther Uranday was part of the 1965 strike. Later, she ran the union’s Membership Department, was in charge of accounting for the Robert F. Kennedy Medical Plan and served as an administrator of the Roger Terronez Clinic. She is now executive assistant to Arturo Rodriguez.

When the 1965 strike occurred, my family and I were working for the D.M. Steele Co. (later it became Tex-Cal) in Earlimart under the supervision of the foreman Joe Mendez. The major buzz around town was whether or not we would join the Filipinos on strike. Everyone was undecided and there was a lot of tension around town on what would happen next.

Finally, my father-in-law, sister-in-law and I broke the news to our foreman, Joe Mendez. I am sure it wasn’t a huge surprise since that is all anyone seemed to talk about during that time. We then headed off to the union office in Delano and spoke to Cesar and Dolores. It was then that I was the first one to sign the declaration of strike against our company. We were then to wait on things while the strike details were sorted out.

As I recall we didn’t go on strike right away, on September 16. In fact it was a few days later that we went to a town hall meeting where everyone in Earlimart happened to be there. The vibe and energy were amazing. The hall was decorated with union flags and pictures of Emiliano Zapata.

Cesar began speaking and told us all about the Filipino union, AWOC, and what they were after. There was a vote held and people started shouting “Strike! Strike!” It was at that moment that the imminent had become reality.

A few days later, on September 20, we met up at one of our co-workers house at around 3 a.m. We were discussing strategy and how to began our strike and make our presence felt. Gilbert Padilla was the picket captain, and it was right there and then that we left as a caravan to the growers’ home.

Our first encounter was with the John Pagliarulo & Son farm. From there we headed off into several other farms, picketing and showing our demands. I am sure it must have been quite a sight for all those growers to see these farm workers waking them up at 3 a.m., ready to do battle with them. It must have been quite a wake up call.

* * *

Roberto Bustos was an original 1965 striker and captain of the 400-mile march from Delano to Sacramento in 1966.

I’ll always remember Cesar coming into the office one day and saying, “We are going to go to Sacramento.” I was very enthusiastic about the idea and was already loading up my car with all my things, and then he gave me the harsh news that we would be marching from Delano to Sacramento! At that moment I thought the man had lost his mind. I looked at the map and saw that the journey was 245 miles.

I didn’t think I could walk that distance, and I was right. Ultimately it came close to 400 miles since we made several stops in different towns and never went on a straight path. We stopped at Ducor, Terra Bella, Visalia and Fresno, among others.

But the day the march started, March 17, 1966, I had no idea of the impact this journey would have. We were expecting support but never to be joined by 10,000 supporters as we arrived at the Capitol in Sacramento. It was overwhelming seeing so many people join us and support us in our struggle. When we had started on our way up we only had 70 farm workers with us. The march took a total of 25 days and finally finished on April 10, 1966.

We walked over 15 miles a day, every day. At times I thought we wouldn’t make it. In fact, had we not been given new boots by a company in Porterville we probably wouldn’t have.

The march was very significant and not just because it was a chance for the governor to see what we were going through. It also allowed the rest of the nation to pay attention to what was happening in Delano. Before the march we had no press coverage whatsoever. It was as if 5,000 workers were not on strike.

Today I leave with the honor of not just being captain of the march but with the legacy and history of what the march signified?the recognition the American public gave to the farm workers struggles.

* * *

Kathy Murguia was a student at the University of California, Berkeley and left everything behind to join the Delano grape strikers in their fight for social justice. She served for years with the UFW.

Primaramente, gracias, thank you, to the United Farm Workers for making this reunion possible.

The role of the volunteer. What comes to mind? In the case of La Causa, the roles volunteers played were varied, but simple: Show up, be present and listen. And try to envision Cesar’s dream of building a union. Then communicate and work very hard to make things happen. We did whatever was needed, went where we were asked and paid close attention because we were all learning some incredible lessons. And, as we all know, this made for some interesting stories.

For example, in the early days, John Shroyer riding the rails to report back to Delano where the grape shipments were headed so they could be boycotted at their delivery point. What John didn’t know was how cold it could get up in the mountains. With teeth chattering, he’d call to check in during a switching operation. John Shroyer was a volunteer

We could be organizing a rally at Berkeley and counting the cash while riding with Cesar and Wendy Goepel to the next rally, then shadowing a semi loaded with grapes with John Leggett and calling Dorothy Kaufman to show up with pickets.

We could be stuffing envelopes with Helen Chavez for the annual credit union meeting, then driving to deposit check donations at the local bank while making the all-important RC soda run. We could be helping Fina Hernandez sort out donations of food and clothing in the morning and later writing the endless thank you letters for Cesar. Then there was Ida Cusino with her vibrant challenge to the strikebreakers, “Do you have a heart?” We could be baby-sitting Dolores’ kids, then driving to Richgrove to deliver food to a family on strike.

Then there were the picketlines, the forever picketline. During the workweek, waking up before dawn, the quiet stillness urging us to get out there before the scabs showed up. To once again stand with Manuel, Elizer and Mike Vasquez, the Zapatas, the Urandays, the Herreras, Marcos Munoz, Gilbert Padilla, the Cadenases, the Saludados, Epifanio Camacho, Roberto Bustos, Pete Cardenas, the Hernandezes and on and on?to ask workers to leave the fields, join the union or work elsewhere, while Eddie Frankel in his Navy Pee coat carefully listed the number of scabs working and those who left. There was the Hirsch family, Jenny organizing Jerry Cohen’s office, Liza and Fred helping organize.

This was the life of a volunteer.

We could be shoveling chicken manure and later meeting with Cesar with a new assignment of driving to Texas to help Gilbert Padilla take on the Texas Rangers.

Being a volunteer also was to be eloquent: Rev. Dave Havens reading [Jack London’s] “Definition of a Strikebreaker.” Or dead serious: Jim Drake giving the latest boycott report at the Friday night strike meetings. Or humorous: Augie Lira, Senor Cantu, Carolina Vasquez and Luis Valdez with the Teatro, entertaining us with their songs and actos depicting the absurd and cruel antics of the labor contractors, growers and sheriffs.

Then there were the jails, both inside and out: Taking depositions, being fingerprinted and booked, showing up to pick up strikers. Jerry Cohen meeting a deadline for a response to a temporary restraining order. Tom Dalzell posting bail for strikers. Marshall Ganz with his clipboard making notes and giving assignment. LeRoy Chatfield grappling with Service Center finances. Jessica Govea singing to the souls of all of us while doing the research for a viable Service Center and medical plan. Nurse Peggy McGivern giving primary care to strikers. Marion Moses arguing with hospital staff over access to medical care for strikers. Dr. Jerry Lackner tending to Cesar’s back problems. Dr. David Brooks working to educate strikers on how to stay healthy. Nick Jones caring for Huelga and Bocyott, and organizing Cesar’s security detail. Doug Adair, Marsha Brooks and Bill Esher getting the real story and working endless hours to publish and distribute the Malcriado. Donna Haber and Donna Childers dealing with Cesar and Dolores’ endless paper work. Fathers Eugene Boyle and Mark Day, Reverends Chris Hartmire, Phil Farnham, Jim Drake, Gene Boutilier and David Havens ministering to the souls of the strikers. Sue Minor, their anchor in the Los Angeles Migrant Ministry office. And through the camera’s lenses of John Lewis, John Couns, George Ballis and Manuel Sancehz, our images were captured and given to history.

These were the volunteers. Andy Zermeno’s charactures of Don Sotaco transformed into Senor Compesino as the movement gained momentum.

We were sustained in the early days with food from Fina’s kitchen, Menudo on Sunday mornings and a pitcher of beer at People’s, compliments of Ann and Mocha. Later we were given the $5 weekly stipend. We slept in our cars, on the floors of the office and on cots at the Pink House. In time, thanks to increasing donations from the churches and unions, we had our own house. We were a messy group because who had time to clean?

The roles we assumed ultimately became who we were. We were the farm worker volunteers and ultimately we crossed the country went to the big cities and to Europe and Canada, and with the workers told the world the story of the farm workers struggle. We had justice on our minds, La Causa in our hearts and El Movimiento in our feet and hands. And in our souls, faith that it could be done. Si Se Puede!

* * *

The Grape Boycott

Leroy Chatfield worked with the union from 1963 to 1973, playing a key role in Cesar Chavez’s 1968 fast for nonviolence and running the Los Angeles boycott that brought victory in the grapes in 1970. Chatfield was also an original member of the state Agricultural Labor Relations Board in 1975.

As successful as the 1965 strike was, I am sure we wouldn’t have been able to accomplish what we did had it not been for the boycotts in the cities. The area we struck was just too large for us to have a major impact.

The distance of 60 miles stretched from Ducor to Lamont, and it covered over 400 square miles of territory and had over 30 growers who we were fighting. As if that wasn’t hard enough, the growers began to bring in Mexicans by the truckload to break our strike. That’s the moment when we became very discouraged and knew we had to take another route in order to triumph.

Our solution was to take the fight to the cities. We would boycott the grapes and let people in the cities know what was happening in Delano. At first the boycott and the response were very slow. However, with time things began to pick up and eventually the momentum built and there was a lot of support. It got to the point that the growers started to spread the word that there wasn’t a strike in Delano?yet people were not buying into it.

The boycott could only work if the strike was taking place and vice versa. Had people not been out there picketing [in the fields], the public would have bought the lies put out by the growers. Fortunately for us, people were too smart to allow such manipulation.

* * *

Marcos Munoz was a grape striker in 1965. He also organized and led the grape boycott in the Boston area, which was instrumental in the defeat of the growers.

There is nothing I love more than La Causa. Even my wife knows this. I would go to great lengths to make sure we defeated the growers, even if it meant going to Boston. Of course, I didn’t know this at the time. In fact, I thought I was being sent to Barstow. At least that’s what I had heard. But then I realized I didn’t need a plane ticket to get there. It finally clicked that I was going to the great city of Boston!

A city full of revolutionaries and rebels. The city that is known for throwing the famous Boston Tea Party and dumping all that tea into the harbor during the American Revolution. And although, it was an intimidating task taking on such a large city, especially since I didn’t know how to read or write, I went anyway.

With just a few contact names and a few dollar bills in my pocket, I set out to send the message to the other side of the country. When I arrived there, I was allowed to sleep overnight in a meat packing plant. It wasn’t very comfortable, but at least I was able to shower.

Once I was engaged in the Boston scene, I became aware of the Vietnam War as well as so many civil rights movements at the time. It was during one of this protests that I met an anti-war demonstrator who helped me build a sign for the cause. The sign read something along the lines of, “America: Shame on you for bombarding Vietnam. Help the farm workers instead.” This was just the beginning of a movement that would eventually be embraced by the whole city. People everywhere began to sympathize with what was happening in Delano.

I tried to get my point across any way I could. I remember one certain instance where I filled up a box of stones and had people lift it so they had an idea of the weight [of grape lugs] these farm workers had to carry.

Then in an effort to copy the events of the Boston Tea Party, we emulated the event by dumping grapes arriving from California into the harbor instead of tea. Then Cesar suggested we leave some for Ronald Reagan, who was the California governor at the time and a huge supporter of the farmers. So we sent these smelly, rotten grapes back to California, to the governor’s office.

There was plenty of help from everyone in the city, including the Boston mayor, Kevin White. Mr. White supported us by sending a letter to Reagan warning him that if any more California grapes were to arrive in Boston, he would personally dump them over into the harbor. It was a great gesture and a symbolism of the support we received in Boston.

* * *

Virginia Rodriguez was Cesar Chavez’ secretary as well as the leader of boycotts in Oregon, Minnesota, Kansas City, New England and New York.

I grew up in the San Joaquin Valley with my parents and my seven other siblings. We were a large family, but very tight and everyone had to carry their own weight even at a very young age. As a kid, I had no choice but to work the San Joaquin Valley fields.

My mother would say, “Once you finish school, ask the bus driver to drop you off in the fields because we need your help.” So very sheepishly we would tell the bus driver to let us off in whatever fields they happened to be working at.

I guess that’s where my sense of social justice and nonconformity was born. So one day, when I happened to be browsing the want ads of a newspaper I was immediately drawn to a clerical position that said, “Viva La Causa!”

So just like that my husband, Nick, and I packed up our car with our six-week-old daughter and headed off to Portland. However, the daunting task ahead of us was anything but easy. It meant carrying the message of the farm workers and halting the sale of grapes. It meant mounting enough support and sympathy for a cause that most people could not yet relate to.

For the next two and a half years we went to different unions, community groups and anyone who would listen to our message. I was amazed and overwhelmed by the response. The people in Portland were very supportive of La Causa and went to incredible lengths to help us out.

The moment that will forever stick out in my mind is when we asked a big grocery store to stop selling grapes. We were ignored several times and eventually a group of 100 women, including myself, headed to the corporate offices to speak with the president of the company. But once we got there, we were told he wasn’t in. We never believed such excuses and within the blink of an eye we were raiding every single office in that building looking for the executive suite that would lead us to the president. We never found him, but our desire for justice had no limits.

* * *

Dolores Huerta is a founder of the United Farm Workers and an iconic figure who symbolizes what the movement is all about. She has worked tirelessly for La Causa for more than four decades.

Dolores Huerta is a founder of the United Farm Workers and an iconic figure who symbolizes what the movement is all about. She has worked tirelessly for La Causa for more than four decades.

It is important to remember not just the strike but how it developed. Some people don’t realize that Cesar and I had been organizing since 1962. In fact, I had worked with Filipino leaders like Larry Itliong for a while before we went on strike.

When our Filipino brothers went on strike in Coachella the union only had $70 in its account. Those were the only funds that we counted with. I still recall the evening when we gathered and found out about the Coachella strike. We knew we had to support it. Yet I had seven kids to feed and Helen and Cesar had eight. As we discussed the situation all eyes turned to Helen and without a blink of an eye she said, “Well, we have to support the strike!”

We didn’t know how we would make ends meet, but it didn’t matter because our faith was too strong. I believe there were key moments such as the evening that transpired into Cesar’s struggle and how people put not just their trust but also their wallets in the union.

It was this faith and our belief in justice that allowed us to overcome even the biggest struggles. How else could we get by when we didn’t even have money for gas and our diets consisted of beans and tortillas?

The strike was a very difficult time especially when the growers got injunctions so that we weren’t allowed to picket. We couldn’t even wear shirts that had the word Huelga.

It was around this time that one of the attorneys working with us suggested to Cesar that we start a boycott. Cesar liked the idea a lot and just like that we began the boycott. The plan was very simple: To take the fight into the cities and have the people help us out with one very easy task of not buying grapes.

The difficult part of it all was getting the strikers to the cities. We didn’t even have money for gas. We did whatever we had to do in order to get to the cities, including hitchhiking. Others left for New York City in school buses.

Once we arrived, we encountered even more problems as police began arresting the boycotters in New York City. Fortunately, we were able to get our people out [of jail] when Robert F. Kennedy sent his crew of lawyers to help us out.

Back in Delano we had new enemies: some Catholic priests. Since a lot of these priests were related to the growers, they started spreading propaganda against the strike and started preaching to the workers to stop the picketing.

Fortunately for us, just as we had our share of enemies, we also had our share of friends. These included the Puerto Ricans who taught us how to strike, the Jewish people with their generosity and the Black Panthers who helped out in our boycotts. Without the contribution of all these groups the boycott and strike wouldn’t have been a success.

* * *

Rev. Chris Hartmire, a Presbyterian minister, was longtime director of the California Migrant Ministry (later the National Farm Worker Ministry). He played a key role in rallying critical support for the grape strike and boycott from the nation’s religious community.

By the 1950s, 38 states had migrant ministry programs, mostly non-controversial programs like nursing care, education, recreation day care and vacation Bible schools. These programs didn’t change anything, but they did introduce thousands of church people?mostly women?to the realities of a migrant farm worker’s life.

California was unique. In the late 1950s and early 1960s, all California Migrant Ministry staff?one or two at a time?spent four to six weeks traveling with Cesar and Fred Ross Sr.?or Gilbert Padilla or Dolores Huerta?as they organized chapters of the CSO [Community Service Organization].

By the time of the grape strike in 1965, we in the migrant ministry were fully committed to the dream of a farm workers union. When the NFWA joined the AWOC on September 20, Cesar asked us for help: help in the form of staff, money for gas for the picketline, food for the striker families and delegations of church people to go to Delano.

Jim Drake and Gil Padilla (at that time a migrant ministry staff person) were assigned to Delano full time. [The week of] September 22-23, we organized a delegation of California church leaders who visited the strike and called on the growers to negotiate. Some of you may remember Episcopal Bishop Summer Watters being dusted by a grower’s tractor, not the smartest thing to do.

On October 19, nine clergymen joined Helen Chavez and 34 strikers in going to jail for shouting “Huelga!” on the picketline. On December 13 and 14, 11 national religious leaders, Protestant and Catholic, visited Delano. It wasn’t long before all Protestant denominations were in the middle of a raging internal fight over the migrant ministry and the Delano strike. The church fight went on for two years. We lost most of our supporters in the agricultural valleys but many, many more friends were drawn to the farm workers’ struggle.

When the boycott became the focus of the union’s strategy we sent our staff to cities near and far. Migrant ministry summer volunteers, instead of working with migrant families in labor camps, were assigned to California boycott cities. The grape boycott got official support from the Northern California, national and world councils of churches, the Central Conference of American Rabbis, the Union of Hebrew Congregations and many individual denominations. More and more, religious groups were pulled into the battle by the strikers who went out on the boycott.

When strikers went to churches and synagogues, told their stories and asked for help, few could say “no.” Slowly but surely hundreds, then thousands, of the best folks said “yes.” They opened their homes to house meetings, invited the strikers to more churches and church groups and joined picketlines in front of grocery stores.

In the process they fell in love with the farm workers’ movement and began to do things they could never have imagined: Leafleting stores where their neighbors shopped, sneaking into storage areas to determine what grapes were in the store, joining other clergy and laity in prayer vigils around the grape counters, filling shopping carts and leaving them at the checkout counter, arguing with their pastors and their friends, risking jail and sometimes going to jail. In every city where the boycott was active the churches and the synagogues were engaged.

By coming to Delano or joining the boycott in their city, religious people got turned on to the movement. So much so that they acted, they did, what Marcos and Dolores and Richard and many others [leading the boycott] wanted them to do. And they carried the boycott message into their religious organizations, all the way to the top.

The boycott was a powerful human event for thousands of church folks. It added goodness and meaning to their lives. They, of course, helped the cause. But they received much in return. And when the boycott left their cities, many were literally broken-hearted. If they were here, they would join me in saying, Thank you, a thousand times thank you?to you pioneer strikers and boycotters who challenged us and then led us on the most important and most meaningful ride of our lives.

* * *

Jerry Cohen was union general counsel beginning in 1967. He played a pivotal role in the strike and boycott as well as events leading up to the contract signings in 1970. Later he helped create the 1975 Agricultural Labor Relations Act.

It was July 25, 1970, and I will never forget that day. That evening I got a phone call from a John Giumarra Jr. requesting to speak to Jerry Cohen. “This is he,” I answered. As it turns out John Giumarra wanted to have a meeting that would be “beneficial to both parties.” He said he would call back to arrange a time, and I got in touch with Cesar and Dolores as well and told them what was happening.

Eventually Giumarra called again and again. The last call I received was around midnight. I asked John what exactly he wanted to do and his reply was, “Cohen, I ain’t no legal asshole. I just want the union label.” It was pretty obvious then that he was conceding defeat.

So at 2 a.m. we met John Giumarra Sr. and his team at the Stardust Motel in Delano. When John Sr. came in he said, “Well this little Sicilian put up a hell of a fight but we are ready to talk now.” And just like that, we made a deal almost five years into the strike.

To us it was pretty obvious that the end would come soon. We would be getting reports from all parts of the country of how non-union grapes would just sit on the shelf while the union grapes disappeared in an instant.

The strike had taken a long time but Cesar was very patient and knew that we had to hold out and not just settle for anything. In big part, Cesar’s fast forced everyone else in the union to think creatively and not give into the temptation of using violent methods to resolve the dispute. Ultimately, the fast forced people not to take shortcuts and the easy way out.

Cesar’s ideal, along with the farm workers and volunteers’ work, gave us the power we needed in order to defeat the growers. They dealt us an incredible hand and all we had to do was show the cards.

Now, 40 years after the contract was signed in this very same room where we are sitting today, I have one request to make and that is that the next time you get them (Giumarra), you bring them back here and have them sign the contract in this same room.

* * *

Other voices from the strike

Many other men and women, most of them older and graying, raised their voices to remember days of hardship and pride during the 40th anniversary reunion. Just a few of them follow.

Hortensia Mata was one of the original 1965 strikers.

Back in 1965, I wasn’t aware and didn’t even know what a strike was. That is until the day that Gilbert Padilla came into the field where I worked one spring day in ’65. Gilbert Padilla was a young, tall, amiable man working for Cesar Chavez as an organizer. That day my life was changed forever, Gilbert opened our eyes to the many injustices we were living everyday.

Gilbert said, “There is going to be a meeting tonight at my house and Cesar Chavez will be there to show you how we can change things.” So that night we went to Gilbert’s home and started listening to what Cesar had to say. After listening to him speak in such a calm and decisive manner I made up my mind to go on strike as well. Cesar told us that it would be difficult and to not expect success right away. “In the end we will win,” he said.

Before I realized it, I was on strike as well. I was afraid of how I would make ends meet and how I would take care of basic necessities. I am not sure if my crew was ready, mentally more than anything. The hardships were tremendous, especially when we had nothing to eat. I would sit up all night sometimes just thinking how I would pay off my house and even though it wasn’t very luxurious it was still my family’s home.

The fight in the fields was especially difficult because the police sided with the growers and every time we tried to put something together the police struck it down.

Fortunately for us we always had people to help us out any way they could. A man by the name of Chris Hartmire was one of those kind souls. Chris brought food to all the strikers in my crew, sometimes canned or a hot meal. Whatever it was we appreciated deeply. I am sure that if it hadn’t been for people like Chris, I would have lost my faith.

By the time the San Francisco boycott came around in 1968, I was more determined than ever. I recall packing in a car with my other friends and co-workers and heading off to San Francisco to boycott the grapes up there. I believe that was the key to our success. Had we stayed in Delano no one would have been aware of our struggle. There wasn’t any media coverage in the Central Valley and we finally got the attention we deserved when we arrived in San Francisco.

There was plenty of support from everyone in the Bay Area and it helped tremendously. Suddenly, no one was buying grapes. We had the grape industry cornered. It was all a matter of time before we came to an agreement.

When the day finally came I was extremely proud of all the sacrifice I had made and had no regrets about everything I had to go through. It was during those strike years that I learned invaluable lessons that I still carry to this day. What I will always remember though is that united we can overcome any obstacle including powerful companies and corporations.

* * *

Alfredo Vazquez was one of the original picketers from the 1965 strike.

I first joined Cesar Chavez and went on strike in 1965. Those were very uncertain, very difficult times to get by even on an every day basis. I recall days that we didn’t even have anything to eat and at times we saw no end to the strike.

For me it was the march from Coachella to Calexico that was the most challenging of times. The five-day journey tested not just our physical energy but also our will. However, the march was crucial to ask for the support of the Calexico workers and to join forces with us. We had to make a dramatic entrance in order for the workers to realize how important unity was. So after a lot of discussion we decided to walk the 200-mile course into the fields of Calexico.

Upon our arrival people became extremely excited and we had a lot of support. I could tell that we would win right there and then. For five weeks we fought a battle that at times seemed impossible to grasp, but victory was just a matter of time. We were insulted and provoked by the police. They tried to break us and humiliate us, yet they were not able to succeed. Cesar was very firm that we should not play in to their hands by fighting them because it would only make matters worse. For me that was the most excruciating time. Being battered and insulted just for wanting better working conditions seemed like an inhumane price to pay. After five arduous weeks we prevailed and I believe that march changed the course of not just the lives of people who were directly involved but also of future generations, including this one. Workers now have water and toilets, something that we lacked for a long time.

It was during this time that I really learned the meaning of courage and standing up to those people without violence and not playing into their hands. We were able to gain a lot more sympathy from a lot of people by taking the non-violent route. We focused on the problem, which was workers rights, and not riots or violent uprisings. That is what I am most proud of.

* * *

Jessie De La Cruz was a striker and the union’s first woman organizer. Jessie wrote a biography covering her role in the 1965 strike as well as of her experiences working in the fields for 67 years.

Fear was never an option. That’s what I believed. I knew there was something that had to be done. I became the first woman organizer within the union because I knew I had no choice. From a very early age I had seen it all. I was only seven when I started working the California fields, and after working in the same humiliating conditions for over 30 years, I knew I had to make a stand and show my presence, especially as a woman. During that time working conditions were extremely poor. We didn’t have any drinking water during our workday and no access to a bathroom.

It was during 1964 that I had my first encounter with Cesar Chavez. I listened to one of his speeches about organizing and decided I could play a pivotal part and organize workers as well. Cesar never doubted my abilities. He had a lot of faith in me and the fact that I was a woman never became an issue. That’s how he treated everyone, like equals. Although there were many challenges to overcome, especially at the beginning, I was never discouraged because I knew we would prevail in the end.

I recall getting workers together and having to hear the insults from the Japanese growers. I was called every name in the book and intimidated in every way. But I always had the same reply: “Long live Cesar Chavez!” I think that response always struck a bigger chord than stooping to their level because it showed the faith I had in the cause and that nothing would stop me.

At home things weren’t an better. My husband and I had trouble putting food on the table for our children. We had to take several loans just to make ends meet. But we always stuck together and had help from many different people just to stay afloat.

All these challenges were hard on me, but all of them pale in comparison to one specific incident in 1968. I was called upon to do something I never thought I would do, but I had no choice. As the strike grew and we gained strength, the growers started hiring scabs in order to work the fields. Most of these people were recent arrivals from Mexico and had no idea of all the struggles and hardships we had to go through in order to improve working conditions. I was given no choice but to call the Border Patrol and turn in my own people. It was an awful feeling, like I had betrayed my heritage and the home country of my parents. I tried to convince myself this was for the benefit of everyone, yet I could not help but cry.

But as the year moved along and we started making contracts I became more determined than ever. When the strike finally ended in 1970, I was exhausted, physically and emotionally scarred. It had been five long years but we finally accomplished what we had set out to do.

Looking back on those years I learned many lessons of courage and sacrifice, but if there is one thing I will always take with me it is that nothing gets accomplished without uniting and working together towards a common goal.

* * *

Sunday at La Paz

On Sunday, Sept. 18, La Paz hosted the second day of 40th anniversary events, honoring the contributions of the 1960s volunteers who dedicated some of the best years of their lives to the grape strike and boycott.

A morning ceremony opened with a blessing and brief prayer service at Cesar Chavez’s gravesite set in the beautiful memorial garden of the National Chavez Center. Among those speaking were Paul Chavez, president of the National Farm Workers Service Center Inc., and Virginia Nesmith, head of the National Farm Worker Ministry (successor to the California Migrant Ministry). Fred Ross Jr. led the audience in reading the “Prayer of the Farm Worker Struggle.”

Then a photographic exhibit on the grape strike was premiered in the exhibit halls of the adjacent Visitor’s Center, the old La Paz administration building that was recently renovated. It still houses Cesar’s carefully preserved office and library.

Among photographers whose work is included in the exhibit are Jon Lewis, Jon Couns and George Ballis. Other photos came through the courtesy of the Wayne State University Labor Archives and LeRoy Chatfield. Veterans of the ’65 strike and boycott, particularly Esther Uranday, painstakingly worked with National Chavez Center staff on photo captions that identify by name those pictured in the dozens of photographs.

The photos will remain up until they are replaced next April by a new photographic exhibit depicting the 1966 march from Delano to Sacramento. (The National Chavez Center is open Tuesday-Friday from 10 a.m. to 4 p.m. and Saturday and Sunday from 11 a.m. to 4 p.m. It is closed on Monday.)

Documentary films from the period of the grape strike were shown in the Visitor Center’s state-of-the-art multimedia/conference room (roughly the space occupied by the old administration building’s conference room). An outdoor barbeque lunch was served and Arturo Rodriguez took guests on a tour of the current farm workers’ movement offices nearby (in an expanded building that once housed the La Paz print shop).

* * *

Lighting candles at La Paz

Among those taking part in a blessing ceremony at the gravesite of Cesar Chavez as candles were lighted to remember those who have sacrificed for the movement was National Farm Worker Ministry Executive Director Virginia Nesmith.

A reading from Ezekiel, 22:29-30: “The people of the Land practice extortion and commit robbery. They oppress the poor and needy and mistreat the alien, denying them justice. I looked for one among them who would build up the wall and stand before me in the gap on behalf of the land, so I would not have to destroy it.”

We know that God found those who would stand in the gap. [Candles were lit as names were read.]

Cesar Chavez stood in the gap.

The martyrs, Nan Freeman, Rufino Contreras, Juan de la Cruz, Nagi Daifallah and Rene Lopez, stood in the gap.

The farm workers who had the courage to go out on strike stood in the gap.

And all the volunteers around the country who joined their struggle stood in the gap.

All of us here have committed ourselves in some way to this movement. But let us remember, brothers and sisters, that our commitments are not our own. They have been given passion by Christ. They have been energized by the spirits of St. Francis, the Virgin of Guadalupe, Cesar, the martyrs, the strikers and the volunteers.

Our commitments belong not only to us but to the history of humankind?to those who came before us, and to those who will follow us.

Let us take a moment now to reflect on those who were partners with us in the struggle and who have died or who cannot be here with us today, and to re-commit ourselves now to carry on the fight for farm worker justice in whatever ways we can?to stand in the gap.

* * *

Sampling of Historical Sites at the Forty Acres and Delano

As part of the 40th anniversary, a guide and map was prepared highlighting some historic sites at the Forty Acres and in the town of Delano.

At the Forty Acres

Gas station

Cesar Chavez spent 25 days fasting to rededicate the farm workers movement to nonviolence in February and March 1968 inside a tiny room off the corridor of the adobe-constructed service station facing Garces Highway. Daily mass was celebrated in the adjacent warehouse as well as outdoors, where farm workers established a tent city. It was here that U.S. Sen. Robert Kennedy met briefly with Cesar on March 10, 1968, before driving to Memorial Park in Delano for an outdoor mass marking the breaking of the fast.

Union hall

This was where the 40th anniversary program was held on Sept. 17, 2005. It was also the scene for union and community meetings during the last years of the Delano Grape Strike, after the union relocated its offices from Albany Street in Delano. It was here that Delano-area table grape growers gathered to sign their first UFW contracts on July 29, 1970. John Giumarra Sr. held his hands up in mock surrender for the news cameras as Cesar Chavez looked on.

The field office

It housed the union hall and the UFW headquarters from 1968 until 1971, when the operation moved to La Paz. A small room in the northeast corner of the field office (with a single window facing east) was Cesar Chavez’s office.

Paulo Agbayani Village

Agbayani Retirement Village was the farm workers movement’s response to the plight of elderly and displaced Filipino farm workers. Most immigrated from the Philippines as young men in the 1920s and ’30s. No Filipino women were allowed and marriage to white women, including Latinas at the time, was forbidden by California’s antimiscegnation laws. The Filipino farm workers spent their lives in farm labor camps from which they were evicted when they were no longer productive. Unable to marry, most didn’t have families or a place to stay. The Agbayani Village, named for a grape striker who died on the picketline, was dedicated in 1974. Built mission style in a central park-like setting, it had 58 living units, a lounge and common dining room where daily meals were provided. The last Filipino brother was 1965 grape striker Fred Abad who died in 1997 at age 87. Cesar Chavez conducted his last public fast, of 36 days, over the pesticide poisoning of farm workers in a small room at the very southeast corner of the village in summer 1988. The facility still offers affordable housing to low-income area residents, many elderly.

Quonset Hut

On the east side of Mettler Ave. just northeast of Forty Acres is an old Quonset hut that became a strike kitchen and warehouse/distribution center for donations of clothing and food for the grape strikers during the early years of the walkouts.

In the city of Delano

Our Lady of Guadalupe Church hall

On Mexican Independence Day, September 16, 1965, the mostly Latino membership of the National Farm Workers Association met in the hall next to Our Lady of Guadalupe Catholic Church in west Delano. There, they voted to join a strike against Delano table and wine grape growers begun on September 8, 1965, by the Agricultural Workers Organizing Committee, composed largely of Filipino American farm workers. NFWA members joined the picketlines four days later, on September 20, 1965.

Filipino Hall

It became a joint strike hall and kitchen for members belonging to both the National Farm Workers Association and the Agricultural Workers Organizing Committee. The hall was a place where Latino and Filipino strikers met and ate together. Car caravans hailing from distant parts of California and across the country regularly brought food and clothing to Filipino Hall to aid the strikers. “Community meetings” were held in the hall on Friday nights throughout most of the five-year strike. During his first visit to Delano in March 1966, Senator Robert F. Kennedy spoke to the strikers in the hall after attending a Senate subcommittee hearing in Delano.

Missionary church

This missionary church building at Garces Highway and Belmont Street served as the site for the strikers’ Friday night meetings and performances of the Teatro Campesino before they moved to the Filipino Hall.

102 Albany Street

The union’s first offices, including Cesar Chavez’s office, were housed here. It was also home to other union operations, including the El Malcriado newspaper, the Membership Department and Hiring Hall. Union scouts would radio in reports of strikebreakers showing up inside struck vineyards so pickets could be dispatched from this address. Shortly after the strike began in 1965, shots were fired into cars parked in front of the building. Behind 102 Albany Street, at First Avenue and Asti Street, was the “Pink House,” so-named because it was painted pink. When the Delano strike began, it was home for some strikers left without a place to live. Later it served as headquarters for the grape boycott. Next to the Pink House was another former residence that served as the first offices of the National Farm Workers Service Center Inc.

People’s Store and Cafe

The rambling building covers half a city block along Garces Highway and was the longtime site of a market (still there) with old-fashioned gas pumps in front. Next-door was a bar with pool tables that became a gathering place for union members during the 1965 Delano Grape Strike. The corner store was where Cesar Chavez began courting Helen Fabela, who worked the market cash register, after they started seeing each other in the mid-1940s.

1221 Kensington Street

Cesar and Helen Chavez and their eight children moved into the house just next door (to the north of) 1221 Kensington in early 1962, after they made the decision to begin a farm workers union. Within a short time the family moved to larger quarters next door, where they lived until relocating to La Paz, Keene, Calif. in 1971. The small wood-frame house at 1221 Kensington had two bedrooms?plus a third converted from a lean-to in the rear of the structure?and one bathroom.

321 Austin Street

Dolores Huerta and her family lived here from 1963 until 1970. The home hosted a day care and grocery center and it was where leaflets were run off before the union’s office was established at 102 Albany Street. Dolores also put up many union volunteers in her house.

Delano High School auditorium

Sen. Robert Kennedy’s first trip to Delano was in March 1966, to attend a hearing at the high school auditorium conducted by the U.S. Senate Subcommittee on Migratory Labor examining the Delano Grape Strike. After listening to Kern County Sheriff Leroy Gaylen testify how he had arrested a large group of peaceful picketers because the grower threatened to “cut their hearts out,” the New York senator admonished “the sheriff and the district attorney to read the Constitution of the United States.”

Stardust Motel

Room 44 at the Stardust Motel (now the Travel Inn) was where, in July 1970, a small group that included Cesar Chavez, UFW General Counsel Jerry Cohen and John Giumarra Jr. and Sr. met to negotiate the union contracts that ended the five-year Delano Grape Strike.

Memorial Park

On March 10, 1968, after Cesar Chavez and Sen. Robert Kennedy met briefly at the Forty Acres where Cesar had been fasting for 25 days, they drove to Memorial Park in Delano where the fast was broken during a mass held in the middle of the parking lot and attended by thousands of farm workers and union supporters.

Casa Hernandez

With 81 units of one- and two-bedroom garden-style apartments featuring full amenities including washers and dryers, Casa Hernandez provides highly affordable housing for seniors. Rents for one-bedroom units begin at $215 a month; two-bedroom apartments start at $255. The National Farm Workers Service Center Inc. facility, which opened in 1999, boasts a central community room where numerous meetings, activities and services are hosted, plus an active seniors program, including flu shots and screenings by health care providers. Named for Julio and Fina Hernandez, founding members of the United Farm Workers and leaders of the 1965 grape strike, Casa Hernandez is located in west Delano, directly across the street from the union’s first offices.