The Passion of César Chávez

The Catholic community in America is at present politically adrift. In this presidential election year, candidates continue to strategize over how to win the Catholic vote despite any number of studies that continue to reveal that there is no Catholic vote. Catholics run the rather narrow American gamut from liberalism to conservatism, in percentages that reflect the roughly 50/50 split of the general U.S. electorate. The HHS mandate on contraception, the most blatant political assault on the Catholic Church since the rise of the public education system, has failed to rally Catholics into a united political front. Even worse, the American bishops who have heroically opposed the mandate have as yet been unable to find any distinctively Catholic way of addressing the problem. It is one thing to invoke the constitutional protection of religious liberty; it is another thing entirely to present oneself as doing no more than defending the U.S. Constitution. The development of an authentic Catholic politics in a pluralist society requires an ability to speak a common language with non-Catholics even as one tries to lead them beyond the lowest common denominator to a fuller understanding of a distinctly Catholic position open to people of good will. For all of its heroism, the pro-life movement has failed to accomplish this essential rhetorical task.

The Catholic community in America is at present politically adrift. In this presidential election year, candidates continue to strategize over how to win the Catholic vote despite any number of studies that continue to reveal that there is no Catholic vote. Catholics run the rather narrow American gamut from liberalism to conservatism, in percentages that reflect the roughly 50/50 split of the general U.S. electorate. The HHS mandate on contraception, the most blatant political assault on the Catholic Church since the rise of the public education system, has failed to rally Catholics into a united political front. Even worse, the American bishops who have heroically opposed the mandate have as yet been unable to find any distinctively Catholic way of addressing the problem. It is one thing to invoke the constitutional protection of religious liberty; it is another thing entirely to present oneself as doing no more than defending the U.S. Constitution. The development of an authentic Catholic politics in a pluralist society requires an ability to speak a common language with non-Catholics even as one tries to lead them beyond the lowest common denominator to a fuller understanding of a distinctly Catholic position open to people of good will. For all of its heroism, the pro-life movement has failed to accomplish this essential rhetorical task.

The last Catholic in America to achieve this cultural/political synthesis was César Chávez.

Chávez was a labor leader who organized a union to secure decent wages and working conditions for the largely Mexican and Mexican-American agricultural workers of California in the 1960s. At the peak of his influence, he rivaled Martin Luther King as a national spokesman for social justice. No number of well-intentioned film strips with cartoon pictures of Martin Luther King and John F. Kennedy could disguise the fact that King was a Baptist minister from the South; as a Catholic school boy in the 1970s, I was taught to see Chávez as a kind of Catholic MLK, a great national figure that we could call our own. Sadly, he is now largely a forgotten figure even among self-styled “progressive” Catholics, who have never been able to overcome the language barrier presented by Chávez’s Spanish-speaking world and who, despite sentimental posturing, have largely followed the liberal mainstream in abandoning the old Catholic commitment to labor justice in favor of an emphasis on issues of race, gender and sexuality. The secular Left, in turn, has long had trouble with Chávez precisely because he was an orthodox Catholic and refused to allow his movement to be co-opted by Marxist ideology or the neo-pagan identity politics of the Chicano movement.

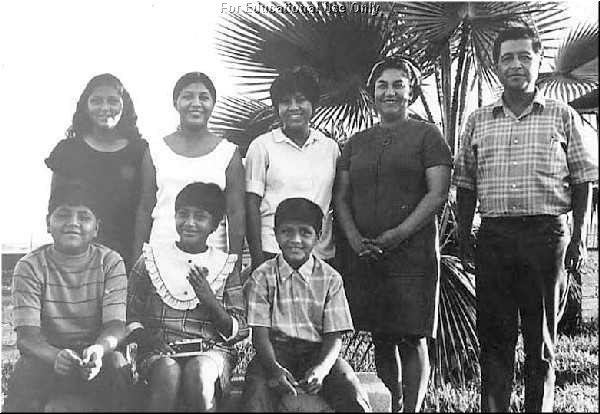

Chávez was born on March 31, 1927 in Yuma, Arizona. His parents operated a small grocery store and supplemented income from the store by farming a small plot of land. They lost all their property in the Depression and were forced to take up the life of migrant farmers in California. This was a time of tremendous labor unrest among agricultural workers in California; in addition to the class oppression immortalized by John Steinbeck’s account of Okie migrants in Grapes of Wrath, Chávez faced the additional challenge of having brown skin and speaking Spanish. World War II provided a temporary escape, as Chávez joined the Navy in 1944, but by 1946 he had returned to civilian life—and migrant farming. Like many returning soldiers, he soon married. He and his wife Helen (Fabela) did their part to contribute to the postwar Baby Boom, having four children between the years 1949 and 1952, and four more in the years that followed.

They lost all their property in the Depression and were forced to take up the life of migrant farmers in California. This was a time of tremendous labor unrest among agricultural workers in California; in addition to the class oppression immortalized by John Steinbeck’s account of Okie migrants in Grapes of Wrath, Chávez faced the additional challenge of having brown skin and speaking Spanish. World War II provided a temporary escape, as Chávez joined the Navy in 1944, but by 1946 he had returned to civilian life—and migrant farming. Like many returning soldiers, he soon married. He and his wife Helen (Fabela) did their part to contribute to the postwar Baby Boom, having four children between the years 1949 and 1952, and four more in the years that followed.

A stable marriage and a large family mark the limit of the Chávez’s participation in the postwar American consensus. When not traveling for agricultural labor, Chávez and his family lived in a section of San Jose call Sal Si Puedes, meaning “get out if you can.” In San Jose, Chávez came under the mentorship of an Irish-American priest, Father Donald McDonnell, who introduced Chávez to the social encyclicals of Pope Leo XIII and Pius IX. Despite the range of challenges presented by the urban poverty of San Jose, it was the papal endorsement of labor unions that fired the political imagination of the young Chávez. The cooperation of McDonnell and Chávez followed in the line of the great lay-clerical alliances of the labor movement of the 1930s, such as Charles Owen Rice and Philip Murray among steelworkers in Pittsburgh. Yet from the very start, there was a distinctively Mexican cultural difference to Chávez’s labor activism. Father McDonnell had built a mission church in honor of Our Lady of Guadalupe, and la Guadalupana would serve as the patron saint of Chávez’s movement. Images of Nuestra Señora de Guadalupe would remain a constant visual presence in marches and strikes that followed Chávez’s initial politicization under McDonnell.

In 1962, Chávez organized the Farm Workers Association (FWA) as a self-help organization to assist farm workers struggling with low wages, poor housing and working conditions, and general hostile treatment from the grape growers of central California. By 1964, the organization had successfully formed a credit union, but Chavez’s ultimate goal was for the FWA to secure recognition as a union representing farm workers in collective bargaining negotiations with the grape growers and other agribusiness interests of California. Opposition to unionization was strong among the growers, and agricultural workers remained in an ambiguous relation to the federal labor laws guaranteeing American industrial workers the right to collective bargaining. In the mid-1960s, the Civil Rights activism of Martin Luther King and President Lyndon Johnson’s declaration of a War on Poverty inspired Chávez with hope for positive change in the situation of Mexican American farm workers. Although in tune with national events, Chávez would root his politics in distinctly Catholic ideas and practices. King had his march to Selma; Chávez would make his pilgrimage to Sacramento.

In 1962, Chávez organized the Farm Workers Association (FWA) as a self-help organization to assist farm workers struggling with low wages, poor housing and working conditions, and general hostile treatment from the grape growers of central California. By 1964, the organization had successfully formed a credit union, but Chavez’s ultimate goal was for the FWA to secure recognition as a union representing farm workers in collective bargaining negotiations with the grape growers and other agribusiness interests of California. Opposition to unionization was strong among the growers, and agricultural workers remained in an ambiguous relation to the federal labor laws guaranteeing American industrial workers the right to collective bargaining. In the mid-1960s, the Civil Rights activism of Martin Luther King and President Lyndon Johnson’s declaration of a War on Poverty inspired Chávez with hope for positive change in the situation of Mexican American farm workers. Although in tune with national events, Chávez would root his politics in distinctly Catholic ideas and practices. King had his march to Selma; Chávez would make his pilgrimage to Sacramento.

In 1965, Chávez had helped to organize a strike on the part of agricultural workers in California. The growers responded with the usual tactic of bringing in strike-breaking, scab labor from other regions of California and Mexico. Chávez knew how this tactic often led to violent confrontations that only discredited striking workers. Committed to non-violence yet thwarted at the point of production, he sought to challenge the growers at the point of consumption through a national boycott of table grapes (the tactic of the boycott itself has origins in the struggle of Catholic tenant farmers against Protestant landlords in Ireland). Still, Chávez believed that his cause needed something more than material tactics, but rather some symbolic action to call attention to the deeper spiritual values at stake. To this end, he organized a pilgrimage from Delano, a town at the center of California’s grape growing region, to the state capitol of Sacramento to demand government support for the struggle of the farm workers against the growers. In his “Plan of Delano,” Chávez spoke of the desire for social justice, but deflected the impulse toward righteous indignation by describing the “Pilgrimage to the capital of the State in Sacramento” as an act of “penance for all the failings of Farm Workers.” With a Catholic understanding of the sacredness of place and time, Chávez chose a route that carried his pilgrims on the “very same road . . . the Mexican race has sacrificed itself for the last hundred years. . . .This Pilgrimage is a witness to the suffering we have seen for generations.” The Pilgrimage was timed, moreover, to arrive in Sacramento on Easter Sunday, the day of resurrection.

Chávez’s selection of symbols reflected his awareness that while speaking for a largely Mexican Catholic constituency, was also trying to speak to a broader American public. His “Plan of Delano” reflects a proper ordering of these symbolic allegiances:

We seek, and have, the support of the Church in what we do. At the head of the Pilgrimage we carry LA VIRGEN DE LA GUADALUPE . . . because she is ours, all ours, Patroness of the Mexican people. We also carry the Sacred Cross and the Star of David because we are not sectarians, and because we ask the help and prayers of all religions.

All men are brothers—sons of the same God; that is why we say to all men of good will, in the words of Pope Leo XIII, “Everyone’s first duty is to protect the workers from the greed of speculators who use human beings as instruments to provide themselves with money. It is neither just nor human to oppress men with excessive work to the point where their minds become enfeebled and their bodies worn out.” GOD SHALL NOT ABANDON US.

The symbolic politics of the Pilgrimage dramatized the dignity and plight of the farm workers to the point that one of the major grape growers, Schenley Industries, agreed to negotiate a contract with Chávez’s union.

This victory was short-lived, as another corporate giant grower, Di Giorgio, used the Teamsters to try to take control of the union so as to serve corporate interests. By 1968, this conflict once again threatened to introduce violence into the movement. In response, he undertook a fast to call himself and his followers back to the spiritual roots of their struggle. Though most associated at the time with the activism of Gandhi, fasting of course has a long tradition in Christian spirituality as well. Chávez insisted that he did not use the fast as a pressure tactic so much as an act of spiritual discipline, an effort to see the world more clearly. He conducted the fast in a small storage room in a service station, which he called his “monastic cell.” He surrounded himself with images of the saints and Our Lady of Guadalupe, and lived only on the Eucharist. These religious practices alienated many of his secular followers, but earned him a visit from no less a public Catholic than Robert Kennedy, who was soon to announce his candidacy for the presidency. On March 11, 1968, Chávez broke his fast by breaking bread with Kennedy.

The next few months would see the assassinations of both Martin Luther King and Robert Kennedy. As two dreams died, Chávez continued his struggle. By 1970, he had secured favorable agreements with a majority of the grape growers in California. After five years, the grape strike and boycott ended in success.

This was hardly the end of the fight for Chávez. Grape growers continued to use the Teamsters to muscle in on Chávez’s union, while the late 1970s and 1980s saw a general decline in organized labor across America. Some within the movement criticized what they perceived to be his increasingly authoritarian manner, yet Chávez remained true to his principles to the end. That end came, fittingly, as a result of yet another fast he undertook in connection with yet another labor battle. In April of 1993, he traveled to Arizona to assist workers battling a lawsuit brought by a lettuce grower. Despite the objections of many of his supporters concerned for his health, he subjected himself to a fast. His followers finally prevailed upon him to break the fast. A few days later, he died in his sleep. May his memory not die in ours.